1_23 E-Votional

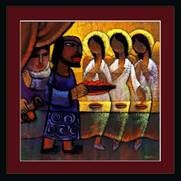

“Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it.” - Hebrews 13:2

Our theme this week in worship is hospitality and we will focus on a story from Genesis 18 in which Abraham and Sarah show hospitality to “strangers” who turn out to be angels in disguise revealing a divine message of great importance to them. The conclusion from this story, echoed in Hebrews 13:2, is clear: we never know exactly how, when, where and in whom God may show up and pay us a visit. Being hospitable to others is a way of ensuring that we don’t miss that message.

At a regional youth event, probably 15 years ago by now, I sat with a group from our church during the opening worship in the hotel’s grand banquet room. We were sitting on the far-left hand side of the audience, approximately half-way back. A praise band performed, different speakers spoke words of introduction about the weekend’s theme, and we (in the audience) were standing up and sitting down quite a bit. All throughout this time, I happened to notice a strange man. He was dressed in what looked like “coveralls” – some sort of uni-garment – with a stocking cap on his head. Even from way off, one could tell his clothes were old and dirty. He would walk slowly throughout the banquet room, shuffling his feet, and sitting down every so often. After a few minutes he’d get up, shuffle on a little more and sit down in another open seat. Once he even shuffled over to an empty seat in the row in front of us, before continuing on.

When it came time for the keynote speaker to give the opening address, this man was shuffling his way near the stage. I’m sure I was not the only one who was, by now, wondering who this guy was and why he was in the room. But as the minister at the microphone completed her introduction and spoke the keynoter’s name, the man in the coveralls climbed the stairs, turned, took off his hat, unzipped and stepped out of his uni-garment and introduced himself as the featured guest.

Perhaps, as you were reading these words just now, you could see where this was leading. But his point that night was clear. While he admitted that no one treated him poorly or asked him to leave the banquet room, no one approached him, asked him his name, offered a chair to sit in, or showed him anything else that we might consider a gesture of kindness, mercy, compassion or hospitality. It was, rather, as though he were invisible.

As Christians, we live in the world and yet we are not of the world. In the world, we are (sometimes rightfully) wary and skeptical of strangers. Yet those cautionary instincts cannot prohibit us from our higher, not-of-the-world calling to show hospitality to strangers – not to withhold things like kindness from them. For who knows? We just might be welcoming into our lives a message from God that we most need to hear.